La Surréalisme dans l'art américain

Featuring nearly 180 works and over 80 artists, this exhibition showcases the extensive surrealist and post-surrealist collections of French and American museums, alongside private collections.

The exhibition explores the history of surrealist trends in American art from the 1930s to the late 1960s, rather than recounting the notion of New York artists so thunderstruck by the arrival of the surrealist painters that they were moved to invent an intrinsically American art movement, Abstract Expressionism, that surpassed Surrealism and relegated it to a rather limited past.

It begins in Marseille, in 1940-41, with a group of surrealist artists gathered around André Breton and waiting to leave for the United States. As they awaited their visas for the new world—with Villa Air-Bel a central gathering place—Victor Brauner, Max Ernst, Jacqueline Lamba, André Masson and Wilfredo Lam formed a compact group that took part in collective gatherings during which they created “exquisite corpse” assemblages and, together, created the famous Game of Marseille.

Though the arrival of some of these artists in New York continues to be described as a revelation for young local artists, the exhibition emphasizes how surrealist artworks had been exhibited since the early 1930s on both the East and West Coasts of America and had become extremely popular, catapulting Salvador Dalí, in particular, to stardom. What’s more, they had garnered some disciples, leading to the development of an intrinsically American Surrealism with such leading lights as Joseph Cornell, as well as largely unknown figures of New York Social Surrealism (such as O. Louis Guglielmi) and Californian Post-Surrealism (such as Helen Lundeberg).

During the war years the European surrealists, in exile together on the East Coast, continued to make art, sometimes with significant changes. Their presence inspired young local artists and gave rise to a transatlantic Surrealism with renewed forms and practices, with two variants that would gradually diverge: one figurative, one abstract. Transatlantic Figurative Surrealism, spearheaded by artists such as Dalí, Cornell, Man Ray, Yves Tanguy, Kay Sage and the filmmaker Maya Deren, comprised a deeply dreamlike dimension that incorporated some exponents of fantastic neo-romanticism, such as Pavel Tchelitchew. Transatlantic Abstract Surrealism—one of the key protagonists of which, Arshile Gorky, was ordained by Breton as a surrealist in his own right, and which is therefore a particular focus of the exhibition, with major paintings and drawings—gradually spawned a movement that critics would call Abstract Expressionism.

The exhibition features surrealist-esque works by preeminent abstract expressionists, including Robert Motherwell, Barnett Newman, Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, David Smith and Clyfford Still, alongside the semi-abstract paintings by Joan Miró that influenced them. It also embraces fringe elements of the group, such as Richard Pousette-Dart and Louise Bourgeois, with their constant emphasis on subjective content driven by metaphor and metamorphosis, as well as the surrealist-influenced abstract work produced on the West Coast by the members of the Dynaton collective (Gordon Onslow-Ford, Lee Mullican). Abstract Expressionism was suffused with Surrealism, despite its key supporter, the critic Clément Greenberg, decrying the Surrealist movement as “academic art under a new literary disguise”. In a way that could no longer be referred to as Surrealism—by now considered outdated—but which nevertheless followed its approach, the 1950s also saw the return of hidden images in the work of Motherwell and in that of Helen Frankenthaler, who features in the exhibition in an unexpected light, given that her work has been cloaked in a discourse that highlights only its abstract nature.

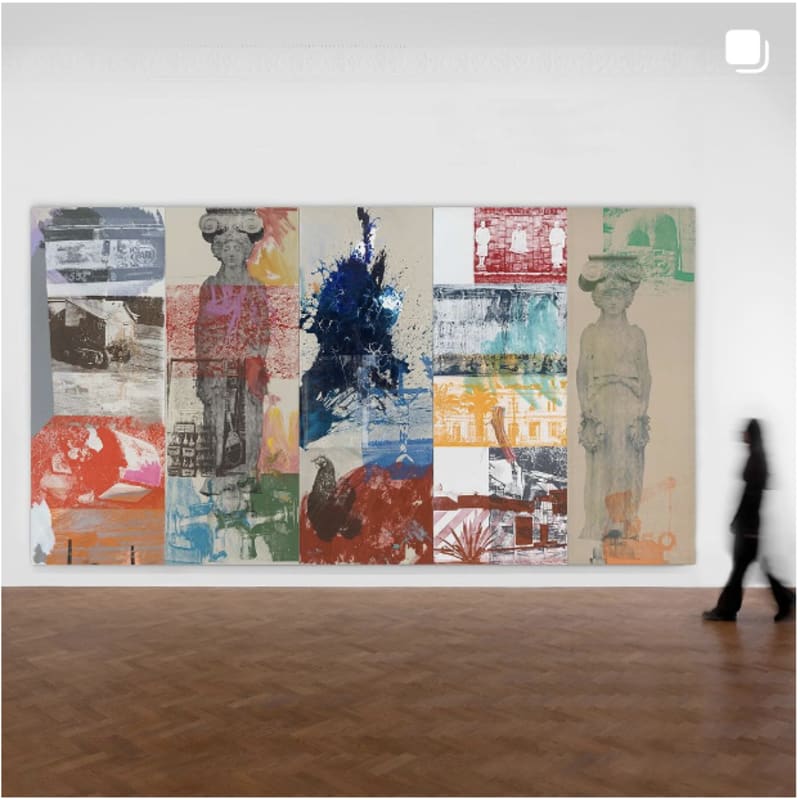

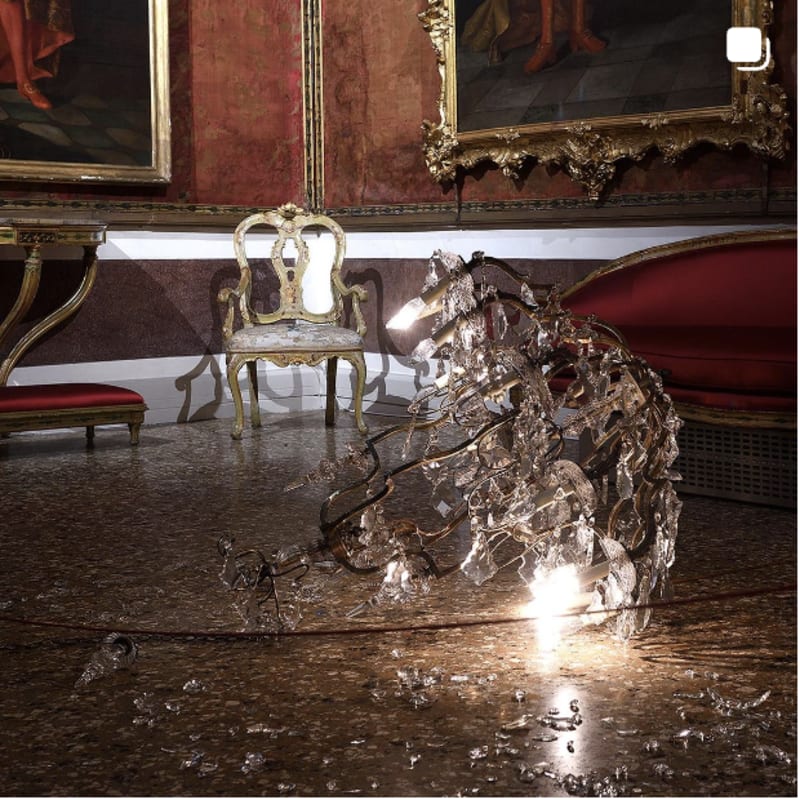

The exhibition then examines the ways in which surrealist methods and strategies were kept alive by American artists until the late 1960s, even if few of them acknowledged it. Rather than lining up a succession of distinct movements (Pop, Minimal, Post-minimal and Conceptual), it cuts across a variety of oppositions caused largely by the breakaway, reductionist inclinations of a small number of critics and promotes a more global tendency that unites both well-known and underrated artists, by presenting what the critic and exhibition curator Gene Swenson referred to in 1966 as “the other tradition”—one he felt was rooted in Surrealism. Despite the diktats of Greenberg and his disciples, Surrealism remained an active force, asserted in provocative ways in the 1950s and 60s (in order to stand out from the critical discourse of the East Coast) by Californian artists such as Wallace Berman, Bruce Conner, Jess and the filmmaker Kenneth Anger, whose work employs metaphor and narration, often with sexual content. On the East Coast, as Swenson pointed out, a new “relationship between object and emotion” was also a central preoccupation among artists such as Jasper Johns, Ray Johnson, Robert Morris and Claes Oldenburg, whose work is sometimes dubbed “neo-Dada” but who can also be called post-surrealists, insofar as their strategies involve using day-to-day objects—alone or combined with others—to convey complex meanings and metaphors, a legacy of the surrealism exemplified by Marcel Duchamp in particular. A selection of boxes created by these artists, as well as the Chicagoan sculptor H. C. Westermann, demonstrates the enduring influence of Duchamp, who remained in the United States after the war ended, his presence silent yet inspiring. From the early 1960s, surrealist elements were also revived by painters such as James Rosenquist and John Wesley, whose paintings are juxtaposed with those of Magritte and Dalí.

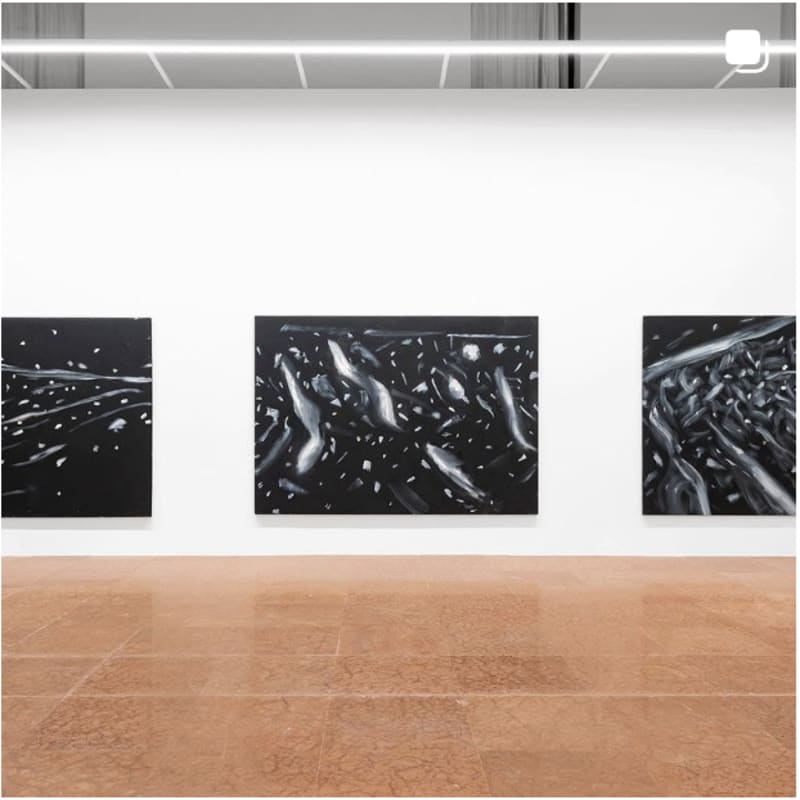

In the late 1960s, at a time when Surrealism was not only the subject of publications and retrospective exhibitions but also experiencing a strong resurgence in popularity—as evidenced by Californian psychedelic rock posters, a selection of which is on display—it also had an underground influence on artists who blurred the boundaries between abstraction and figuration, imbuing their work with a powerful erotic or even sexual charge, creating limp, unsettling forms such as those produced by Alberto Giacometti or Tanguy. Though some of these artists—particularly Bourgeois and Eva Hesse—were grouped together by the young critic Lucy Lippard under the umbrella term of “eccentric abstraction” and classed within a surrealist lineage, the United States witnessed a much wider revival of surrealist themes and methods, from Paul Thek’s meat reliquaries to Nancy Grossmann’s sadomasochistic heads, from Oldenburg’s soft, sagging, sculptures to Lee Bontecou’s aggressive reliefs, and even Richard Serra’s early work. This surrealist heritage was no doubt too scandalous for critics and art historians to acknowledge; instead, they chose to classify these artists into very distinct movements, as if to purify them. The exhibition Surrealism in American Art aims to restore their original impurity and subversive force.

Curated by Eric de Chassey, director of the National Institute of Art History (INHA) in Paris and professor at the Ecole normale supérieure de Lyon, supported by Lucas Roussel, curatorial assistant, with Xavier Rey, heritage curator and director of the museums of Marseille and Guillaume Theulière, curator.

Set design: SALUCES