Sean Scully at Houghton Hall Interviewed by Bryan Appleyard

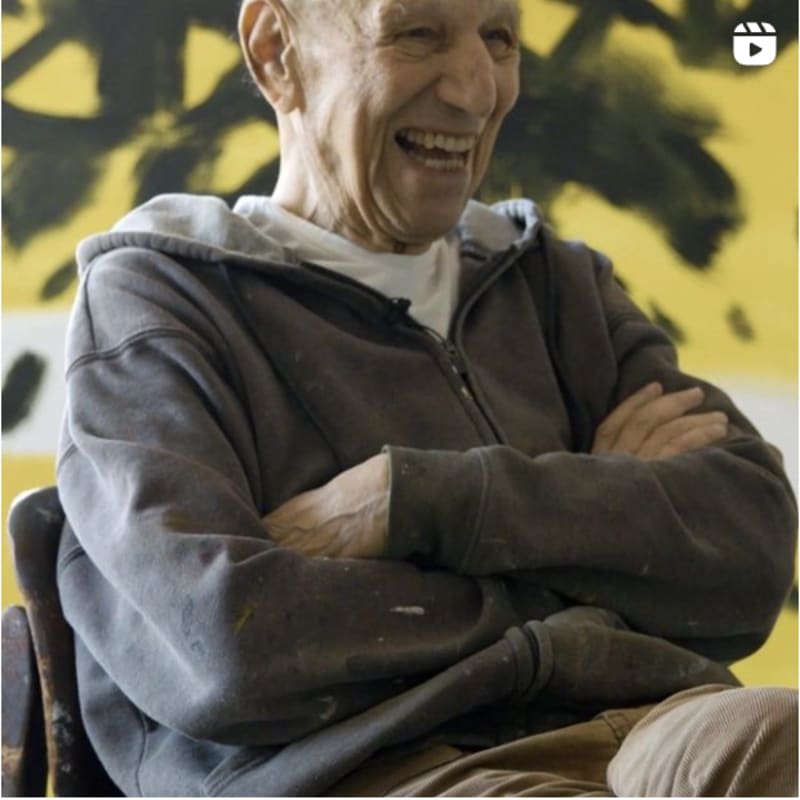

Twice American cops have pointed their guns in Sean Scully’s face. This doesn’t usually happen to world-famous artists. “The police,” he tells me, “are extraordinarily dangerous in America.”

He’s tough, though, brought up in the postwar slums of the Old Kent Road, in southeast London. And there’s something tough about his art. He is, as the great critic Robert Hughes once put it, “one of the most toughly individual artists in America”. But the guns were too much. “I can’t have that for my son. I’d be having a nervous breakdown.”

Scully is 77 and on his fourth marriage. His second son, Oisin, is 14; his first son, Paul, died aged 18 in a car accident in 1983.

“My paintings darkened. It was like turning off a light switch. I did therapy . . . and therapists say fatuous things like ‘time will heal’. Time doesn’t heal. It doesn’t heal at all. It doesn’t help in any way. You are nailed to the wall, and you’ll never get off.”

He now talks a lot about Oisin and does everything he can to protect him. He moved his family to a town a few miles north of New York and away from the guns when Oisin was three.

His new home is in Tappan, which he describes as the oldest town in America. The restaurant where George Washington dined is still there. It is a peaceful place, just what Scully wanted.

Oisin is not allowed on the school bus; Scully drives him. They are learning French together. They are very close. “I take him wherever he wants to go. We stick together, we play penalties together in the back garden. He’s interested in football. We got football boots together.”

Tough, certainly, but tender. He gives away $1 million a year and corresponds with the 300 children he helps to look after remotely in south Asia. “I only taught my son two things. Never break a promise, because that’s what you are. That’s all you are. And never fail to help somebody who can’t help themselves.

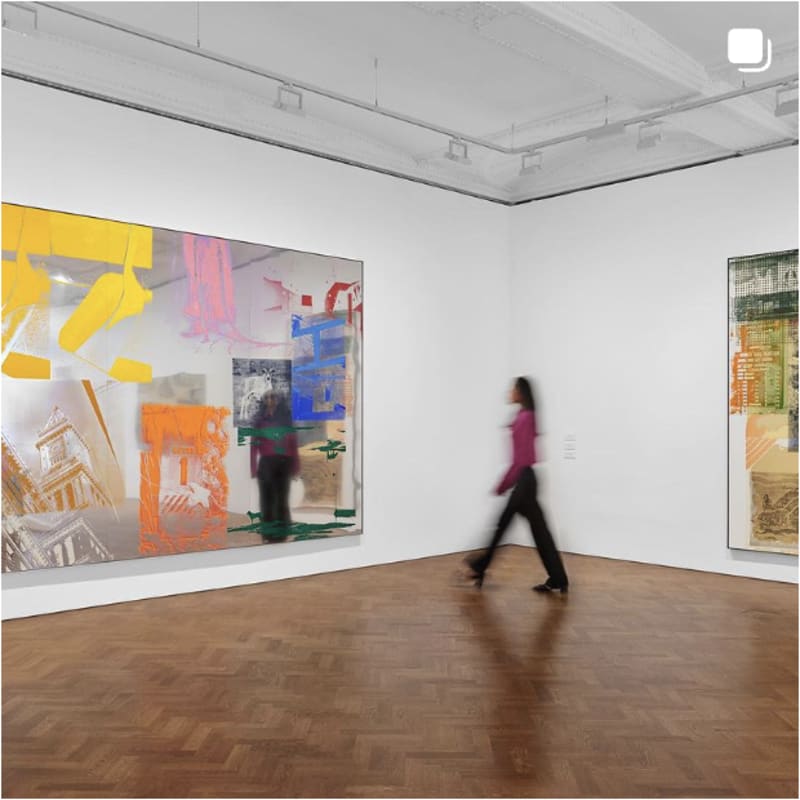

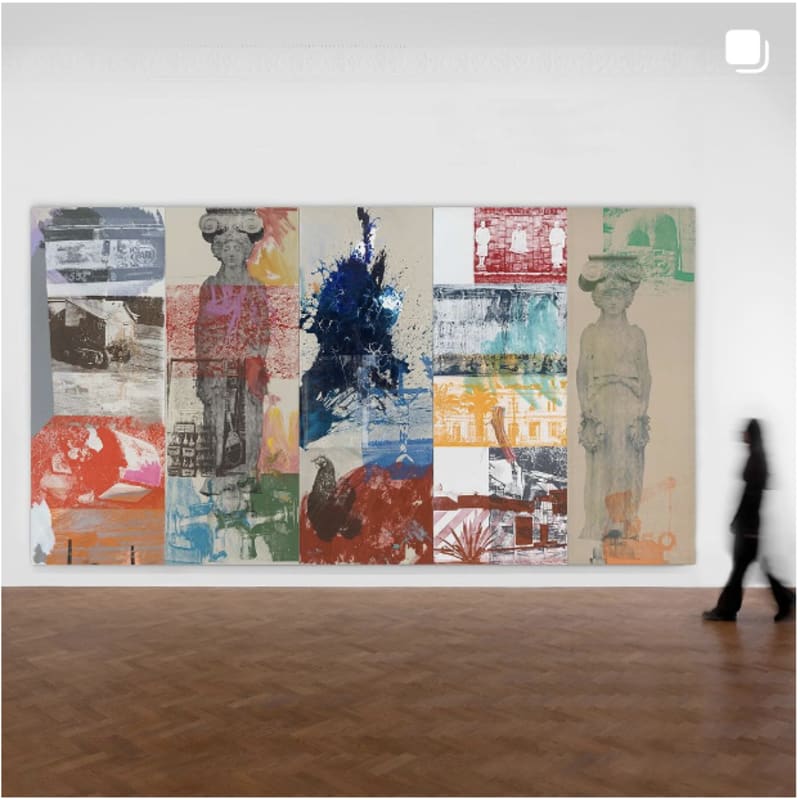

He is a giant in the arts world and we are about to be reminded of that with Smaller Than the Sky, a huge exhibition at Houghton Hall in Norfolk, and the unveiling of a new sculpture, Landline London 2022, a 17ft tower of marble blocks in Hanover Square, London. These although he once said: “England is a country that basically doesn’t understand art.” Really?

“Oh no — they have no clue. It’s a great country, England. I love England. And I know it like the back of my hand. Half my family is from Durham and Scotland. They’re not an extreme people . . . But, you know, the great paintings were made largely on the Continent, I would say. I think that’s fair.”

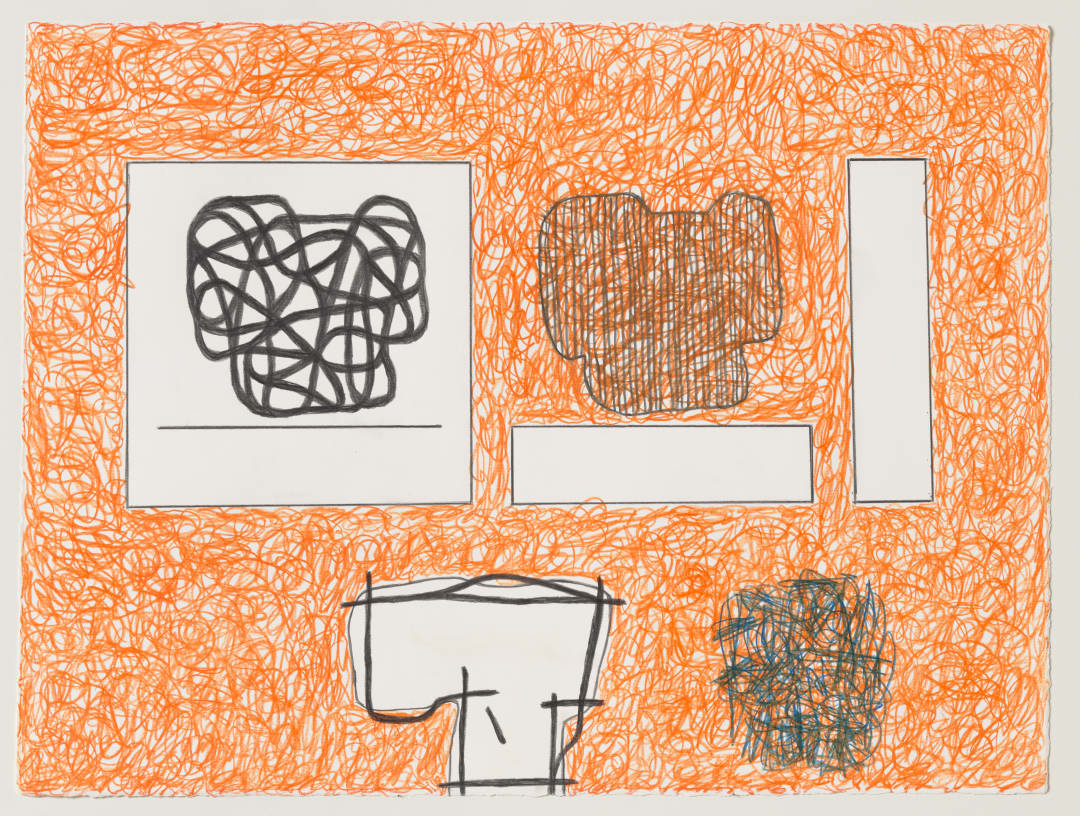

His own art is abstract, lines and rectangles of superbly controlled colours, and his sculptures are similarly disciplined. He did stray from abstraction — to paint Oisin. He is a feeling painter, a modernist romantic. He rejects the coldness of the previous generation of minimalists and especially of Andy Warhol. The mention of the name brings out the street-fighting man of the Old Kent Road.

“It’s this inhuman mirror. That is brutal. And that squeezes out all rumination, all doubt, all questioning, all tenderness, all romantic feeling. It just smashes it. And a soup can is a f***ing soup can and here it is in these colours. Yeah, Andy — it’s f***ing great, isn’t it? No. It’s not f***ing great.”

He is often compared to another great colour-obsessed abstract painter, Mark Rothko. He also rejects this. “My nature is actually not like Rothko’s. He was a sedentary, depressive man. His paintings are really suprematism squeezed through Turner. They both were very obdurate painters.”

He came from nothing — “a damned terrible upbringing”, he called it. It made him a radical, not in a good way. “I was a real commie bastard. I used to do political art — against Vietnam and against apartheid and all that, and we adored Bertrand Russell. We were the Bertrand Russell groupies. And that’s what I knew about Trafalgar Square, I didn’t know a f***ing thing about the National Gallery.”

His mother was a vaudeville singer and his grandmother, who had come over to London with six daughters and one son, bought little scraps of transparent film to stick on the windows of her house in Highbury. Colour grabbed him and has never let him go. He especially adored his grandmother.

“You can imagine what a journey that was from Clonmel, down in Tipperary, with a stop-off in Dublin. She came to London and rented this house on Highbury Hill, No 82. Which I have on various occasions tried to buy, of course. I’m more like Proust, I think, than Beckett.”

He left London for New York in 1975 and is still a big Arsenal supporter. He scoops up his phone and gives me a Zoom tour of his studio, then leads me out into the garden. This five-acre garden is the heart of this passionate man.

He did not move far from New York, but he entered another world. He has recreated, he says, Giverny, the garden that dominated Monet’s latest and greatest paintings. And he has done so in defiance of his neighbours.

“I ban chemicals. Around here you have these spooky lawns that are spooky green. You know, nothing can be that green. They’re like Ronald Reagan’s hair. They kill all the insects, which means that they’re gonna kill us, and they get rid of all errant growth, which means clover — and I let all the clover grow, the bees love it. I tell them all this. They have these lawns that don’t look right, you know. They look like movie stars that have had 400 facelifts.”

I point out, tentatively, that the lawns of Houghton, where his new exhibition is being installed, are pretty damn manicured. Might not the owner, the Marquess of Cholmondeley, be a little upset?

“Well, yeah, it’s not for me to say. I mean, I’m a funny Irish person because I have no rancour towards the English aristocracy at all. I think the monarchy is a good thing.”

He has planted trees by the score and there’s a Buddha in his garden. We have come to the masses of clover. His phone is swooping crazily. “Look, a bee! It’s the first bee! What a beautiful big bee!”

Somebody once said of Scully that “there was something in him that was unstoppable”. I hope that is true. I hope he never stops.